Conversations on Cognition and Control

Historian of science Flora Lysen interviews filmmaker and researcher Richard Ramchurn about his latest artwork The MOMENT. Through storytelling that can sense and adapt to the viewer's physiological and emotional state, Lysen and Ramchurn discuss the potential of technology, the body and the brain.

Flora: I am very happy to be able to engage with Richard Ramchurn’s work as part of The Downloadable Brain programme. My background is in media studies and the history of science and I am particularly interested in (media) histories of the brain and the mind sciences. Over the past few years, I have become enthusiastic about artists speculating and critically reflecting on what we can do, or should do, in this fascinating interdisciplinary domain of brain science. I think artists have the capacity to experimentally intervene into scientific domains in a generative way, the potential to be both critical, poetic and ambiguous in their relation to academic research.

Richard and I share an interest in exploring how the activity of the brain can be mediated and modulated; and specifically how we can learn from artistic experiments with brain measurements, such as EEG devices. EEG is the abbreviation of the word “electro-encephalography,” a technique that measures the electrical activity of neurons that was invented by the German scholar Hans Berger in 1929. In my own historical research, I talk about how EEG, in the early decades of the twentieth century, immediately sparked visions of transparent brains and mind control. In the 1930s, there was a big scientific exhibition in Paris that showcased EEG and speculated that this marvellous but puzzling technology might allow people to open doors or push buttons by means of thought command.

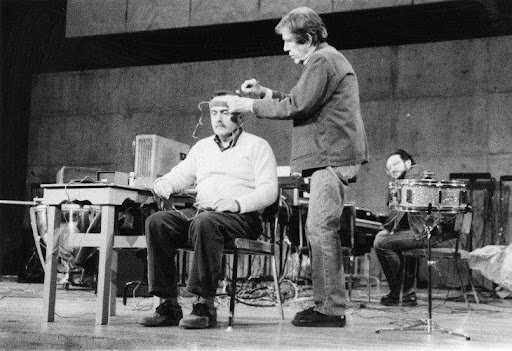

In the late 1960s, artists also started experimenting with EEG technologies. The most famous example is the work of the American artist, Alvin Lucier. In 1965, Lucier wore EEG-electrodes taped to his skull on stage, with wires that were connected to musical instruments around him. He created a kind of feedback loop between the musical environment and his changing brain activity. Throughout the 1970s, there were a number of artistic and scientific experiments (predominantly in the US) that created visions of human brains, bodies and machines that integrated such communication circuits. These systems were viewed as operating on intuitive and unconscious levels, allowing humans to attain new mental states. EEG-artworks were thus part of a particular social and political moment: shaped by a new interest in altered states of mind, but also by new military-funded research into human-machine feedback loops.

I think it is important to keep this longer history of visions and experiments in mind when we look at a new surge of interest into BCI (brain-computer interfaces) artworks. I am curious to hear Richard speculate on how his work ties in with broader hopes and hypes surrounding media-technology, the brain and art-science interaction.

Q&A Flora Lysen and Richard Ramchurn

Flora: How should we understand “control” in a “brain-controlled film” that seems to be steered unconsciously?

With this first question, I want to encourage you to talk more about what we just experienced in watching [The MOMENT]. Reading about the installation in the various articles you published on the piece, I saw you have described it as an example of “brain-controlled (interactive) cinema.” After seeing this first version of the film, we are all of course curious in what way has the brain controlled various elements of the film? Could you explain a bit more about the neuroscientific and technical background to [The Moment]? And can you say something about the word “control,” why do you use this term? How does control operate when it is done unconsciously?

Richard: In terms of control, it builds on the interactive design of my previous film [The Disadvantages of Time Travel] where we really explored this concept of surrendering to control. [The Disadvantages of Time Travel] used attention, meditation and blink data from the Neurosky headset, which together mapped out this space of intentional and awareness of control. As people became immersed in the film, they would forget about any control they had. But then, by doing something like blinking and the film cutting in response, it would bring back their awareness to the agency that they had.

The blink is a semi-autonomous mode of interacting which we do automatically. I was inspired by T. Walter Murch’s book [In The Blink of An Eye] where he speaks about editing a film and argues ‘A thought was like a shot, and a blink was like a cut’. When he was editing his films, his actors would blink at the same time that he would want to cut between shots. Looking a bit more into the literature surrounding neurocinematics and the concept of event segmentation, there is sometimes a signal where people would say one action ends and another action starts. If you put a cut there it would feel natural. It would go unnoticed if the edit was at this point, at this event segmentation.

It got me thinking ‘with this limited device that picks up attention data, could I use that to look at events or to segment activity’? My thought was if someone is watching a shot in the film, and they are wearing the neuro headset, their attention will go up as they concentrate on what they are watching and seeing. At a certain point, their mind is going to wander, and their attention will shift and start to drop. My hunch is that this event segmentation happens at the point of that peak attention. By putting the cuts at each peak of attention then the film will flow from shot to shot following this natural ebb and flow of attention.

It comes down to this effect of ‘control’ that you can have on media. I am doing some work around trust and autonomous systems, such as self-driving cars. How do these systems remove agency from the driver or the person interacting with these robots or objects? How can they work together? Keeping that human in the loop without actively asking that person to be in total control.

Flora: Could you speculate on how [The MOMENT], as an artistic experiment, may help to pose new questions about human cognition and perception, particularly about how cognition and perception might change in relation to new media?

This question is directed towards the neuroscience behind [The MOMENT]. I would love to know how you see this artistic experiment as a way to come up with new questions about human cognition. You have explained a bit about how EEG-measurements steer the cutting of a scene. In this sense, the viewer “becomes an editor” of the film, but this editing is done unconsciously, by means of brain activity. In the past fifteen years or so, researchers in the field of “neurocinematics” have argued that neuroscientific research into cinema viewing can help to understand cognition and perception.

Researchers now started wondering if our brains have somehow changed in relation to particular media. Perhaps our brains have developed new forms of “event segmentation” because we are adapting to a new Netflix and Youtube age. Brains change because of media and media change because of our brains - I think this might be one of the central ideas behind the Cognitive Sensations program. What I find interesting about [The Moment] is that you are creating a direct feedback loop between changing brains and changing media. What type of questions do you think we can pose about human cognition because of this artistic intervention? If you could do any scientific experiment you wanted, what Moment-inspired experiment would you start?

Richard: What’s interesting to me is machine learning algorithms using computer vision to assess emotion and how that can be used or misused, such as creating machine learning libraries to find out if someone is likely to commit a crime. I’ve been reading up on companies with computer vision programs that can recognise the ethnicity of a person, and make judgements based on who knows what these machine learning algorithms are by design opaque. There is more and more literature on the fact that the premises of such computer science experiments are unjust and should be resisted and refused.

The thing with EEG or brain data is that they have to get a device on your head, but when it comes to how a system can tell what your interior state is, it really depends on the quality of the technology. Computer vision can detect small changes in your skin tone, blood flow in your body, elevated pulse, facial muscle features. From this, the algorithms can judge if you’re excited or disgusted. A company may want to see when somebody is excited by their product, or a police state could say ‘oh I want to know if you are disgusted by this crime or these people, or if you sympathise with them just by looking at it’, and I don’t think these are farfetched. There are journalists who have said that it is used in certain countries at the minute. There are so many amazing things that can happen but there are also dangerous and harmful applications as well.

My current interactive film project [Before We Disappear] is a movie that watches you. The narrative is about climate change and how desperate people may get if we continue on our current course. The research involves creating an unbiased machine learning algorithm that detects changes in the viewers’ engagement and uses that data to drive an interactive film. And importantly how this can be done while preserving the viewers privacy. Hopefully I can bring attention to how this technology is being put out in the world for good but also for quite a nefarious purposes.

Ramchurn, R. (2018) Film Still from “Before We Disappear” [image]

Flora: (How) does [The MOMENT] present a type of speculation and what speculative scenario are you offering the viewers?

On the one hand, you have mentioned [The Moment] might be seen as an example of media experimentation that moves away from “homogenised media culture” and that can “break the mould of traditional storytelling.” On the other hand, you also mention that in the future, using BCI and brain data for “media personalisation” may also lead to unwanted influence over our lives in times of surveillance capitalism. Could you say more about how you position this artwork in relation to our present moment of ubiquitous gathering and selling of data and also about how you, as an artist, relate to speculation about a (positive or negative) future in your work?

Richard: I see that happening in a slow process, regarding how we interact with media via algorithms. Companies will roll out different ways of interacting with Youtube or Prime and you don’t know if it is only you that is seeing it or if it is a little experiment.

I wrote about it in early 2017. Trump had just got in, there weren't these militias in America running about, but I think the beginning of the Cambridge Analytica scandal had just happened. I was speculating that if someone did perfect BCI, people could communicate at the speed of thought. At the same time we are still in the same state as we were back then with false media posts and disinformation. What would the repercussions be if people could just think their tweets? How would someone experience their life if it came to that? One wrong thought and you’ve got a twitter storm on top of you. I don’t really see BCI being perfected in the near future, but in the same sentence you see Facebook have developed a way of writing words from neural data. You’ve got transhumanists who are on the boards of Facebook and Google, and Kurtzwell writing about the singularity - that is going to filter through to their products.

Flora: Is [The Moment] contributing to hype and “wishful worries” about mind control?

In our conversation before this event, Richard and I quickly agreed that there is much hype around brain research, that scientific discoveries about the brain might often be overstated. Hype is also omnipresent in the domain of BCI research. Stories about BCI often exaggerate about what such interfaces are able to “read” about our thoughts and emotions. In your work [The MOMENT], you also sketch (cinematic) visions of a future in which experiences can be forced upon the mind with a type of brain device. And the set-up of this EEG-based work also suggests a future in which brain activity may be captured to change our media-experiences. Both of these visions – of mind control and brain-media-interfaces – may lead us to believe that such developments are possible based on the scientific and technological knowledge we have now. Such “wishful worries” (David Brock) may also strengthen our belief in the plausibility of a technology. I would like to ask you to reflect on this issue of “neurohype” and speculative ethics in relation to your own work. How do you – or DO you – resist it?

Richard: The NeuroSky is a single sensor, it is super low resolution and the attention algorithm is black boxed. As it is proprietary to NeuroSky they don’t say how they got the machine learning working. There have been a number of papers which have used that attention measurement and matched it to a visual attention, but the data is interesting. There is another company ‘Emotive’, and they had a six-sensor headset. It is a bit more sci-fi looking and they changed to a subscription business model so that your data goes to their cloud servers, which they hold onto and you can use. This subscription model is appearing with the whole data economy. With data becoming the ‘new oil’, it's becoming harder to own your own data.

I was actually at a marketing research conference at the very beginning of my project, and I came across some real hostility from market researchers thinking that they had missed the boat. I have heard researchers joke at conferences ‘Oh if you want to do some new research just choose an old study and stick a BCI on it.’

There is a new wave of research using physiological data such as EEG and fNIRS because of the proliferation of small accessible sensors. I think when the sensors are good quality and the algorithms are transparent, you can do some really good research and discover a lot from the data.

Biographies

Flora Lysen is a historian of science, fascinated by the circulation of scientific images and stories about new research discoveries. For example: how do researchers think new media might be changing our bodies and brains? Can AI help human eyes to see more in medical images? Analysing the past and present of such narratives helps to understand how current debates about emerging technologies take shape. Flora currently works as a researcher at the Science and Technology Studies (MUSTS research group) at Maastricht University investigating the history of artificial intelligence in image-based medicine. She also works as a tutor at the fine arts MA program “F for Fact” at the Sandberg Institute Amsterdam, a program examining alternative facts, speculative fiction and imagined pasts and futures. Her monograph “Brainmedia: One Hundred Years of Performing Live Brains, 1920-2020,” a book about mediating the human brain in and beyond the laboratory, is forthcoming from Bloomsbury.

Dr Richard Ramchurn is a filmmaker and researcher whose work explores reactive narratives; he creates stories that can sense and adapt to the viewers’ physiological and emotional state. His film work explores race and technology abuses in the Anthropocene. Ramchurn has been creating films and experiences using Brain Computer Interface technology since 2013. #Scanners, a successfully kick-started project became an interactive narrative film called [The Disadvantages of Time Travel] (2014) that viewers controlled via brain data and blinking. This was further explored as a PhD multi award winning research project at the University of Nottingham’s Mixed Reality Lab working with world class researchers in the field of Human Computer Interaction. His most recent brain-controlled film, [The MOMENT] (2018) has been touring internationally, and online since 2018 and covered by international media. His next film [Before We Disappear] is currently in production.